ROBERT STIGWOOD

Music, theatre and film producer, agent, manager

- Simon Napier-Bell

Although his name is known around the world, thanks to his many famous record, stage and film productions, there is surprisingly little biographical information about Robert Stigwood. Despite being one of the richest and most successful figures in the British entertainment industry, most people would probably not even recognise him by sight.

Although he has been one of the most important figures in international music, film and theatre since the early Sixties, his enormous influence and his role in the careers of acts including Cream, Eric Clapton and The Bee Gees has never been examined in any depth; to my knowledge no-one has yet written a biography of him. This is a great gap in the literature because, in terms of his significance on the music scene over the last forty years, Robert Stigwood is (after Rupert Murdoch) probably the single most successful and important Australian in the entertainment business.

Little is known of Robert Stigwood's early life. The commonly known facts are that he was born in Adelaide in 1934 and educated at Sacred Heart College. He began his career as a copywriter for a local advertising agency and then, in 1955, aged 21, he departed Australia for good. He hitched to England, one of the first Aussies to travel to Europe in this way, "pre-empting the hippie trail by ten years" according to Simon Napier-Bell.

He had an eventful trip. In one incident recounted by Napier-Bell, Stigwood bravely climbed fifty feet down a rope ladder into the hold of a tanker to administer morphine to a seaman who had fallen through a hatch. In Turkey, he spent several months living with the family of a young friend in a hut in a small village, working with them in the fields.

When he arrived in England he found a job in what Napier-Bell euphemistically describes describes as as "an institution for backwards teenage boys" in East Anglia. He worked primarily on nightshifts, overseeing the dormitories and "preventing any flow of traffic after lights out". However he found it an "unsympathetic and frustrating job" and left.

Not long after that, he met a young man called Stephen Komlosy. Komlosy went on to manage Lionel Bart, (creator of the musical "Oliver!") and is now a prominent British businessman, but continues his involvement in the arts through the management of his wife, singer and actress Patti Boulaye. He is a member of MENSA and a Fellow of the Institute of Directors. He is also a co-founder of the charity Support for Africa of which he is a Trustee. He is Chairman and CEO of London & Boston Investments, Chairman of Netcentric System Plc and a director of Energy Technique Plc, Croma Group Plc and Avatar System Inc.

Stigwood and Komlosy became fast friends and decided to go into business together. They set up a small theatrical agency and began building up a roster of actors. Among their clients was an a aspiring young actor and singer called John Leyton (who went on to star in The Great Escape and Von Ryan's Express). It Leyton's unexpected success as a recording artist that made both Stigwood and his erstwhile associate Joe Meek into Britain's first independent record producers.

Before the advent of mavericks such as Stigwood and Meek, the British pop music industry was highly stratified. Managers managed artists' careers and nothing else; agents only booked the artists; publishers only published music and sold songs to artists and recording companies, and recording companies recorded, manufactured, sold and promoted the products. It was rare for a manager to also be involved in publishing or agency work and it was almost unheard of for managers, agents or publishers to be directly involved in record production. Recording was still strictly the preserve of the major labels.

This pecking order was typified in the late Fifties and early Sixties by the three dominant figures of British pop -- publisher and manager Larry Parnes (one of the first people to combine publishing with artist management), composer Lionel Bart and the managing director of EMI, Joseph (later Sir Joseph) Lockwood. Typically, Parnes would discover new talent -- as he did with Tommy Steele, Marty Wilde and Billy Fury -- and then sign them to a management contract. Lionel Bart, already under contract to Parnes' publishing company, would write or co-write songs to be recorded and then Parnes would 'sell' the artist to Lockwood and EMI who would sign them to a recording contract, and then record, press and market the records.

But the brief partnership between Robert Stigwood and Joe Meek would change the face of the British recording industry. Robert George "Joe" Meek was a gifted engineer who trained as a radar technician and began his career working for established recording studios in London. By 1960 Meek had accumulated enough equipment to build a studio in his London flat and he began producing records for his own company, RGM Productions.

Meek is credited as the first producer in the UK who had the knowledge and ability to undertake every stage of the record production chain himself. He found the talent -- usually young men with the right "look" and, occasionally, a modicum of talent as well. He found the songs, often co-writing them with collaborators such as Dave Adams or Geoff Goddard, even though Meek himself was reportedly tone-deaf. He recorded the songs at the home studio he had constructed in his London flat, produced the records, had them pressed, then offered the completed product to record companies to distribute. Just before he hooked up with Stigwood, Meek had narrowly missed out on scoring a major hit with the song Angela Jones by Michael Cox because the pressing company he was using was unable to keep up with the demand.

John Leyton was taken on by Robert Stigwood when he was building up his new theatrical agency. Leyton's first major booking was a stint in the TV series 'Biggles', but better roles proved hard to find. Stigwood asked Leyton if he could also sing, and this led to a series of auditions with various recording studios; he was turned down by all of them until he met Joe Meek. Unlike the other companies, Meek was unfazed by Leyton's initial lack of singing experience but was impressed by the young actor's good looks.

Simon Napier-Bell's account confirms that it was Meek who gave Stigwood the idea of make records independently, then getting the record company to distribute it for them in return for a percentage of the of the selling price. It was, as Napier-Bell observes, "the music business equivalent of the independent film production that had changed the face of Hollywood". Excited by Meek's idea, Stigwood gave him one hundred pounds to make the recording. When the record was finished, Meek was reluctant to hawk it to the record companies himself so Stigwood took on the task.

Meek began recording with Leyton in late 1960. His first single, a cover of Tell Laura I Love Her was released in August 1960. It had originally been recorded for the Triumph label, in which Meek had been a partner, but it was leased to the Top Rank label after Triumph folded. Unfortunately, Leyton's single lost out to a rival version by Ricky Valance and his second single Girl On The Floor Above (October 1960) was ignored.

Although Leyton rapidly improved as singer, his chances of a pop career looked slim. But Stigwood's persistence paid off and in mid-1961 he scored a coup when he managed to get Leyton cast in the role of pop star Johnny St. Cyr in a new nationally-broadcast TV series, 'Harper's West One'. Crucially, Stigwood was able to arrange for Leyton's character to perform a song on the show.

Meek's associate, composer Geoff Goddard (whose only previous recorded composition was the Flee-rekkers' Lone Rider) was drafted in to write a song for Leyton to perform on the program. The hastily-penned result was the now-classic Johnny Remember Me, an echo-drenched melodrama in the form of a lover's plea from beyond the grave. The song was featured three times during the course of Leyton's appearance in the series and record shops were instantly deluged with orders.

Because of problems with the supply of earlier records, Meek selected a pressing plant which he knew could keep up with demand, and by the time of Leyton's final appearance they had a monster hit on their hands. The single went to #1 and remained on top of the British charts for fifteen weeks, as well as charting in Europe. It was this success that led Stigwood into the record production andmanagement. He became Leyton's personal manager as well as his agent and then began looking around for other people to manage.

Johnny Remember Me was the first of a string of hit recordings from the Meek/Stigwood/Leyton team, and their success set a new pattern for the industry -- according to Simon Napier-Bell, within a couple of years, over half the hits in the UK were independent productions. Leyton's next single, Wild Wind (Sept. 1961) went to #2, and he scored seven more Top 50 hits over the next two years. But his later chart placings were erratic -- his third single Son, This Is She only made #14 and his fourth, Lone Rider barely scraped in at #40.

Leyton's next two singles Lonely City (Apr. 1962, #14) and Down The River Nile (July 1962, #42) were the last to have any significant input from Joe Meek; Stigwood was evidently becoming dissatified with Meek's work by this time and Stigwood insisted that Lonely City be recorded at a commercial studio. By the time Leyton's seventh single came out, Meek was out of the picture, and all Leyton's subsequent recordings list Stigwood as the producer. From this point Stigwood recorded Leyton at EMI's Abbey Road Studio and while the audio quality improved, the crucial ingredient -- the excitement of the 'Joe Meek sound' -- was lost. Leyton's pop career petered out in late 1964 but fortunately, his movie career had by then taken off.

By late 1961 Stigwood had made a distribution deal with Joseph Lockwood, managing director of EMI, who proved to be the crucial link between the record company and the budding entrepreneur, just as Lockwood had been in the Fifties for Larry Parnes, and just as he would be a couple of years later for Brian Epstein and The Beatles. From his third single on, all John Leyton's singles were released through the HMV label and distributed by EMI.

Leyton was scoring hits, but Stigwood soon realised that there was a major flaw in the deal -- the miniscule percentage that EMI was paying meant that he was barely able to make a profit from these recordings. Nevertheless, the system he pioneered changed the style and direction of the UK pop charts forever and his success with Leyton was instrumental in expanding his business, becoming simultaneously agent, manager and producer, a role he evidently relished.

"He was in every way the first British music business tycoon,

involved in every aspect of the music scene, and setting a precedent that was to become

the blueprint of success for all future pop entrepreneurs."

He became extremely successful because of his control over all almost every facet of the business of his recording artists -- agency, management, production, publishing and concert promotion. His business rapidly expanded and (according to Napier-Bell) Stigwood even bought one of the major music papers in a "fit of pique" when a Stigwood act failed to appear in their Top 30 chart.

The subject of Robert Stigwood's homosexuality and its role in his career is one which has rarely been discussed in any depth. Whether or not it gave him an entree to the British showbiz scene is something probably only he can answer definitively, but it certainly would not have been a disadvantage, considering that so many other important figures in the music industry at that time -- Joseph Lockwood, Larry Parnes, Brian Epstein, Lionel Bart, Kit Lambert, Simon Napier-Bell, Joe Meek, Vicki Wickham, Dusty Springfield -- were also gay.

Music writer Johnny Rogan touched on this intriguing subject in his 1988 book about the British pop scene, Starmakers & Svengalis:

"... I researched the careers of several dozen British pop managers from

the fifties to the present and was surprised to discover that a disproportionately high

number of entrepreneurs from my sample groups fell into one of three categories: gay,

Jewish and male. But what produced this unusual ethnic/sexual equation and why, in the

case of homosexuals and Jews, was it valid predominantly from the early days of British

pop until the late sixties? A broader observation of societal attitudes during those

periods provided some important clues."

"Few would disagree that there has always been a gay tradition in such 'artistic'

occupations as dancing, painting and writing. Even in repressive periods, homosexuals were

accepted by the artistic community, though the nature of their sexuality was often masked

by euphemisms such as 'eccentric' or 'aesthetic'. Historically, the gay movement has also

been well represented in show business and other areas of entertainment. Since British pop

music and traditional show business were inextricably linked, at least until the

mid-sixties, the homosexual network during that period was particularly strong."

- Johnny Rogan, (1988), Starmakers & Svengalis: The History of British Pop

Management", page 276.

It's been suggested that one major reason why so few Australian acts made it in the UK in the Sixties was that they were unable to break into the "Pink Mafia" that supposedly dominated British showbiz. The truth of this claim can never be tested, but it is certainly notable that The Bee Gees, who were far and away our most successful 'home-grown' pop group, owed much of their international success to the fact that they were managed by Stigwood who was, by the time he met them, an influential part of London's gay showbiz establishment.

For a few years Stigwood rode the crest of a wave of success, but according to Napier-Bell, he lived extravagantly and spent lavishly. The small percentages he received from his productions meant that he was largely dependent on agency and management commissions to maintain his cash flow, and gradually his company funds dwindled. Stigwood also promoted concerts "as a quick way to make a buck" and top up the books during slow periods. He specialised in summer seaside promotions, which were sometimes highly profitable, but were also notoriously risky since they often depended on the fickle English weather, among the many other hazards of the business.

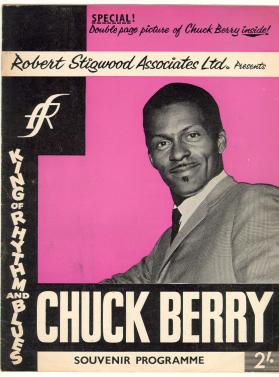

The interest of the audience was one of those hazards, and it worked against him on this occasion. In January 1965 Stigwood promoted a package tour headlined by notoriously 'difficult' rock'n'roll legend Chuck Berry (who famously always demanded payment in cash, up-front) supported by The Five Dimensions, Winston G., The Graham Bond Organization (with Jack Bruce and Ginger Baker), Long John Baldry, and The Moody Blues with guitarist Mike Patto as compere. The tour was poorly attended and adding to his woes, support act The Moody Blues pulled out unexpectedly when the tour reached Manchester (their single Go Now had just gone to #1) and Stigwood had to negotiate with the band to get them back on the show.

The cover of the programme from Stigwood's ill-fated 1965

Chuck Berry tour.

(photo courtesy of the

Mike Patto

website)

Stigwood also lost heavily -- and copped a lot of flak from the industry -- when he over-hyped his latest new pop hopeful, an Anglo-Indian singer called Simon Scott. His heavy-handed promotion included sending out tacky plaster busts of Scott as a promotional gimmick, but it backfired and made the hapless singer into a laughing stock; although Scott finally scored (or was bought) a hit, the venture cost Stigwood a great deal, and it was money that he could ill-afford to lose.

Stigwood's finances ran out halfway through the Berry tour and he called in the receivers, owing some £40,000 to his creditors. EMI offered to bail him out, but he refused because he was anxious to get out of the unfavourable deal he had with the company. He fought valiantly to maintain the illusion that he had kept his personal wealth intact, although in reality he was flat broke. But, according to Simon Napier-Bell, Stigwood managed to fool enough people to keep his creditors at bay while he re-established himself. Within two years, he was was back on top.

Stigwood's aggressive style and his drive to expand his management empire occasionally brought him into conflict with other entrepreneurs. Stigwood is the subject of one of the most famous stories in British showbiz, a fabled altercation between himself and one of the other big movers and shakers of the British pop scene, the infamous Don Arden.

Sometime during 1966 one of Stigwood's staff made the mistake of discussing a possible change of management with of one of Arden's top acts, The Small Faces. Not surprisingly, Arden -- a man you cross at your peril -- took exception to this, and in spite of the fact that Stigwood had never met the group personally, Arden decided to pay him a visit with some of his minders, to teach him a lesson:

Don Arden: I had to stop these overtures -- and quickly. I contacted two well-muscled friends and hired two more equally huge toughs. And we went along to nail this impressario to his chair with fright. There was a large ornate ashtray on his desk. I picked it up and smashed it down with such force that the desk cracked - giving a good impression of a man wild with rage. My friends and I had carefully rehearsed our next move. I pretended to go berserk, lifted the impressario bodily from his chair, dragged him on to the balcony and held him so he was looking down to the pavement four floors below. I asked my friends if I should drop him or forgive him. In unison they shouted: ‘Drop him’. He went rigid with shock and I thought he might have a heart attack. Immediately, I dragged him back into the room and warned him never to interfere with my groups again."

Stigwood took on David Shaw, an ex-City banker, as his partner, giving him access to previously unavailable funds and expertise, and he gained some extra cashflow by subletting his offices to The Who's managers, Chris Stamp and Kit Lambert, although he had reason to regret that decision, becoming the butt of the pair's inveterate and often cruel practical joking.

He kept his Robert Stigwood Agency intact and began rebuilding his career as a manager and independent producer. In 1966 Stigwood made an important connection when he paid £500 to The Who's managers, Chris Stamp and Kit Lambert, for the right to become The Who's booking agent. This gave him the opportunity, soon after, to lure the band away from Decca and onto his own newly established Reaction label, for whom they recorded the famous single Substitute. The recording was done on the sly, and was explicitly intended by the group as a means of breaking their five-year contract with producer Shel Talmy, with whom they had fallen out (the single's original B-side, Waltz For A Pig, was reputedly written about Talmy). Also in 1966 he became the manager of a new band comprising three of the best musicians from two groups that he had under contract -- guitarist Eric Clapton from John Mayall's Bluesbreakers, and bassist Jack Bruce and drummer Ginger Baker from The Graham Bond Organisation.

His connection to The Who enabled him to get his new group, Cream, onto the bill for a major US tour supporting The Who in March 1967. Although the tour was not a great success it was an important showcase for Cream and enabled Stigwood to introduce Cream to New York's music cognoscenti and helped break them in the USA. (It was for this tour that Stigwod commissioned the Dutch art collective called The Fool to paint striking psychedelic designs on Eric Clapton's Gibson SG and Jack Bruce's Fender VI bass.)

However, Stigwood had another pop flop when he tried to promote a singer called "Oscar". Oscar's real name was Paul Beuselinck; his stage name was taken from his father, Oscar Beuselinck, a music business lawyer whose clients included The Who. Oscar had been the pianist in Screaming Lord Sutch's backing band, the Savages; under the name 'Paul Dean' he released two singles in 1965-66. As 'Oscar' he cut four singles for Stigwood's Reaction label. The first, Club of Lights managed to scrape into the lower reaches of the Radio London Fab Forty. The second was a creditable version of a Pete Townshend song, Join My Gang, which The Who never recorded. His third single, a novelty song called Over The Wall We Go (1967) is notable for being written and produced by a young David Bowie, and it gained a degree of notoreity because of Bowie's tongue-in-cheek lyrics concerning escaped prisoners and incompetent cops, which satirised a rash of highly-publicised prison break-outs in the UK. Once again, Stigwood tried unsuccessfully to promote the hapless Oscar with a fake Acadamy-Awards-style statuette. 'Oscar' vanished from sight for some time, but Beuselinck re-emerged in the late Sixties under the name Paul Nicholas. He maintained a connection with Stigwood, performing in the London productions of Hair, Jesus Christ Superstar and Grease, and he also featured in many films; he appeared in Stardust, starring David Essex, and he played the sadistic Cousin Kevin in Stigwood's film version of The Who's Tommy.

Stigwood moved his recording activities to Polydor, where Roland Rennie, with whom he had dealt at EMI, had been appointed as the new managing director. Stigwood had apparently been forewarned that Rennie was moving to Polydor, and this, says Napier-Bell was the major reason that Stigwood had been unwilling to accept EMI's rescue package. Rennie had been a key figure in breaking The Beatles in America; he had been sent to New York by George Martin and all EMI product was channeled through him for distribution by EMI's American partners. It was Rennie who struck the deal to license the first three Beatles records to the Swan and VeeJay lebels, rather than to Capitol, who at first had no interest in the group.

Stigwood signed a much more advantageous deal with Polydor, with high percentages and substantial funding for his recording costs. This gave him the luxury of being able to take Cream to New York, where they cut their records with Atlantic Records' famed house producer-engineer Tom Dowd.

On 13 January 1967 Stigwood signed a career-making deal with his friend and colleague Brian Epstein to merge their two companies. The Beatles were by now off the road, and Epstein was tiring of the demands of his ever-expanding business. He was keen to reduce his involvement in the company he had founded in 1963, NEMS Enterprises, so he eventually struck a deal with Stigwood.

Why Epstein decided to merge with Stigwood is uncertain. There had been numerous other offers made for NEMS over the previous few years and Epstein is reported to have turned down more than one multi-million-dollar offer from American interests, so it is unlikely that he chose to become a partner with Stigwood simply for the money. They knew each other socially and through business, and Stigwood already had a reputation as a shrewd, tough operator, although it appears that Epstein was probably the only person in NEMS who was in favour of the merger.

According to author George Gunby, Epstein told The Beatles' publicicst Alastair Taylor that Stigwood had originally offered to buy NEMS, but the deal eventually became a merger, in which Stigwood would have to put all his company assets into NEMS; in return he would received a reciprocal shareholding in NEMS, plus a salary, an executive position as co-managing director, and access to all of NEMS now-considerable financial and other resources.

It was a godsend for Stigwood, and it effectively placed him at the pinnacle of the British pop industry in one easy step, but Epstein seems ot have been about the only person in NEMS who was keen on the idea. Alastair Taylor is reorted to have exclaimed "You must be joking!" when Epstein told him of the merger. Epstein was also considering handing over his role as manager of The Beatles, but when the Fab Four learned of this they were outraged. They evidently disliked Stigwood intensely; interviewed in 2000 by Greil Marcus, Paul McCartney recalled the group's angry reaction:

"We said, 'In fact, if you do, if you somehow manage to pull this off, we can promise you one thing. We will record God Save the Queen for every single record we make from now on and we'll sing it out of tune. That's a promise. So if this guy buys us, that's what he's buying.'"

Consequently, Epstein stayed on as manager of The Beatles but he handed responsibility for most of his other acts to Stigwood.

The NEMS' staff were also unhappy about the deal. The company had expanded rapidly

growing from fifteen staff in 1964 to eighty in 1966. Epstein had taken over the Vic Lewis

agency in 1965, (bringing in Donovan, Petula Clark and Matt Monroe) and Lewis became a

NEMS director, but many staff members found Lewis' abrasive manner difficult to handle.

According to Gunby:

According to Gunby, Epstein told Derek Taylor that the merger with Stigwood would bring new talent into the fold and would strengthen the operation. Taylor remain unconvinced -- Stigwood, he said, had "a ruthless reputation, a cavalier style that upset more people than it pleased." Epstein himself soon found himself at odds with his new partner -- he was reportedly unhappy about Stigwood's spending, was upset by Stigwood renting a yacht for The Bee Gees, and was also angered by Stigwood's unilateral decision to send Alastair Taylor to America on a business trip, a plan Epstein overruled. It is claimed that Epstein susequently decided that he didn't want Stigwood in the company.

Stigwood's next big break as a manager came only weeks after he started with NEMS. The Bee Gees had recently arrived from Australia with hopes of making it in the UK. Unknown to them, Ronald Rennie had already heard Spicks and Specks thanks to the band's publisher, and Rennie had made arrangements with their Australian label, Festival, to release it in the UK. When, to his surprise, Barry Gibb appeared at Polydor's offices in London, Rennie immediately contacted Stigwood, who he thought would be ideal to sign the group to Polydor and manage them. Robert had just begun his eleven-month tenure with NEMS, to whom Hugh Gibb had sent an LP and acetates in an effort to sign the group to NEMS. Stigwood signed the Bee Gees to a five-year deal in February and took their contract with him when he separated from NEMS in December.

Polydor released Spicks and Specks, but in spite of Stigwood paying for four week's exposure on pirate station Radio Caroline, the single flopped. Stigwood was undeterred, and with NEMS' resources behind him, he embarked on a concerted campaign (no doubt at NEMS' expense) to break The Bee Gees in the UK, assiduously wining and dining TV producers and DJs; according to the MusicWeb Encyclopedia, he spent a whopping £50,000 promoting the group in 1967.

It paid off -- within months their second single, New York Mining Disaster 1941, had become a major UK hit and the follow-up, Massachusetts, went Top 5 in both England and the USA, the first a string of Bee Gees hits through the late Sixties.

Stigwood's companies expanded into almost every field of entertainment. Over the years

the Robert Stigwood Organisation has promoted artists such as

Mick Jagger, Rod Stewart, David Bowie and which managed and forged the careers of acts

including The Bee Gees, Cream, Blind Faith, Eric Clapton and Andy Gibb. Under the RSO

Records label Stigwood recorded artists including Clapton, Yvonne Elliman, Paul Nicholas,

Player and soundtrack albums for the motion pictures "The Empire Strikes Back"

and "Fame" in addition to the films produced by his company RSO Films. By 1968 Stigwood was enjoying huge success with his music ventures -- The Cream

and The Bee Gees were now two of the biggest bands in the world -- but he was in no mood

to rest on his laurels. He moved into theatre production in 1968, and chose his first

projects very wisely indeed.

RSO's transition "from rock management concern to multimedia entertainment empire"

began after Stigwood saw the Broadway production of the pioneering rock musical,

Hair. He decided to stage it in London and it

was a huge success, running for more than five years in the West End. He followed this

with many highly successful productions: Oh Calcutta!, The Dirtiest Show in

Town, Pippin, Sweeney Todd, Sing a Rude Song,

John, Paul, Ringo and Bert (Evening Standard Drama Award best Musical 1974)

and the last of the Tim Rice / Andrew Lloyd Webber musicals, Evita.

Both Superstar and Evita were successfully reproduced on Broadway, the latter picking

up the Tony Award for best Musical 1980. More recently Stigwood produced stage versions

of his two big film musicals, Grease and Saturday Night Fever.

Stigwood moved into both film and TV production in the early Seventies. By this time

the fortunes of his two top acts were waning -- The Bee Gees had broken up briefly in 1970

and for several more years they struggled to regain their former glory; Cream had split in

late 1968; after the deaths of his close friends Jimi Hendrix and Duane Allman and the

disappointing reception of his masterpiece, Layla & Other Assorted Love Songs,

Eric Clapton withdrew into drug addiction.

Stigwood purchased a production company, Associated London Scripts -- the company

which subsequently developed the hit series All in the Family and Sanford &

Son in the USA. In 1973 Stigwood moved into film and produced Jesus Christ Superstar

as a motion picture in association its director, Norman Jewison. He followed this with

the acclaimed film version of The Who's Tommy. Stigwood chose wisely, selecting

iconoclastic auteur Ken Russell to direct. His outlandish visual imagination

provided a perfect filmic setting for the improbable story. His casting raised eyebrows

in some circles but also proved to be ideal for the task. Tommy starred Ann-Margret, Roger

Daltrey in the title role, and featured Elton John, Robert Powell, Jack Nicholson,

Tina Turner, Oliver Reed, Paul Nicholas, Eric Clapton and The Who. It became one of

1975's most popular films and remains one of the most successful mergers of rock music

and film.

RSO Films' next production became one of the biggest hits in the history

of the business -- the colossally successful Saturday Night Fever.

Written by and featuring The Bee Gees, the 2LP soundtrack

album, made music history by becoming the largest-selling soundtrack album

and one of the biggest selling records in history and made the Bee Gees into

international megastars. It was followed by another huge success, Grease,

which launched TV actor John Travolta to super-stardom. Incredibly, the songs

were written 'to order' without the group having seen the film, and according to

Frank Rose's 1977 Rolling Stone article about The Bee Gees, at least four of

the songs -- including Stayin' Alive -- were written in just one week. Although he has enjoyed many great successes, Stigwood

has also had his fair share of flops as a producer. His two music blockbusters were followed

by a rare but infamous miscalculation. In fact, RSO's next film turned out to be one of the

biggest bombs in cinema history -- the execrable Sgt Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band.

On paper, the multi-million-dollar extravaganza looked like a surefire hit -- it featured

the songs of The Beatles, and starred two of the biggest rock acts of the day, Peter Frampton

and the Bee Gees, backed by a staggering list of rock and film greats in cameo parts. Unfortunately

for all concerned, the problems surfaced early and grew steadily worse. Stigwood sacked original

director Chris Bearde before shooting began; the Bee Gees

quickly realised that things did not augur well and begged to be removed from the project, to no avail.

Although the new director, Michael Schulz (Car Wash) did a valiant job, the film turned

out to be a disastrous flop; lampooned by audiences and critics alike,

the unfortunate production is still cited as one of the worst films ever made.

This was followed by the cult 'kiddie gangster' musical Bugsy Malone,

The Fan, Times Square Grease 2, Peter Weir's Gallipoli

(under the R&R Films banner) and the 1997 Golden Globe Awards best film winner,

Evita, starring Madonna. Not all these films were successful however. Moment by Moment, which co-starred

John Travolta and Lily Tomlin, came out only a year after Saturday Night Fever, but

it was panned by critics, bombed at the box-office and is generally credited with

singlehandedly turning one of the hottest stars in the world into 'box office

poison'. Five years later Travolta again displayed his now-legendary inability to pick roles

when he agreed to appear in Stigwood's new film an ill-advised Saturday Night Fever sequel,

directed by Sylvester Stallone. Although perhaps not as bad as Moment by Moment, the movie

was not a success and did nothing to restore Travolta's career, which languished until his ' comeback'

in Pulp Fiction in 1994.

Another curious footnote in Stigwood's career is the rock-musical teen girl 'buddy' movie Times

Square. Stigwood's autocratic streak surfaced again during the making of this film, and director

Allan Moyle was fired during the editing process when Stigwood insisted on cuts that Moyle refused to

make. Stigwood wanted to cut out dialogue scenes to include more music, so he could make the soundtrack a double

album. Stigwood fired Moyle (who didn't make another film for ten years) and made the cuts himself; star

Robin Johnson later said of the result: "It was disappointing. It could've been so much more powerful.

I'd love to see what Allan's cut would've been." Although not successful at the time, it apparently now has

a strong cult following among gay women; the music soundtrack is also of considerable interest; it included

many notable new wave acts -- Patti Smith Group, Pretenders, Talking Heads and Roxy Music and also became

a collector's item for fans of English band XTC because their track, Take This Town, was written

especially for the film and appeared only on the soundtrack LP. Robert Stigwood remains active, primarily in the theatrical musical industry.

He lives at his Barton Manor Estate on the Isle of Wight, off the south coast

of England.

Do you have more information about

Robert Stigwood?

If so, please

EMAIL us and we'll be happy to add your contribution to this page.

PLEASE NOTE: Milesago does not have any contact details for Mr Stigwood or his companies, so don't bother asking. Thank you.

Simon Napier-Bell

You Don't Have To Say You Love Me

(Ebury Press, 1998)

Joseph Brennan

Gibb Songs website

http://www.columbia.edu/~brennan/beegees/67.first.html

The Knitting Circle: Popular Music

http://myweb.lsbu.ac.uk/~stafflag/popularmusic.html

Johnny Rogan

Starmakers & Svengalis: The History of British Pop Management

(Macdonald Queen Anne Press, 1988, ISBN 0-356-15138-7)

Disraeli Gears Cream website

http://twtd.bluemountains.net.au/cream/gears/disraeligears1.htm

Saturday Night Fever - The Musical website

Robert Stigwood biography

http://www.nightfever.co.uk/robert.htm

Meeksville.com - John Leyton pages

http://www.meeksville.com/leytonmovie/

Meek Artistes' Directory - John Leyton

http://www.bigglethwaite.com/telstar/artistes/adir-2.htm

beatlemoney.com

http://www.beatlemoney.com

The Don Arden Story

http://www.elonetwork.com/mrbluesky/donarden.htm

www.45rpm.org.uk - John Leyton

http://www.45-rpm.org.uk/dirj/johnl.htm

Telstar Web - John Leyton

http://www.bigglethwaite.com/telstar/artistes/tw-ley-idx.htm

Mike Patto web page

http://members.aol.com/DThorn88/mike_patto.htm

Moody Blues Tour and Set List project

http://www.toadmail.com/~notten/70_65.htm

Frank Rose

"How Can You Mend A Broken Group? The Bee Gees Did It With Disco"

Rolling Stone, 14 July 1977

Vernon Joyson et al

Tapestry of Delights

http://www.borderlinebooks.com/uk6070s/o3.html#Oscar

Jenni Olson

"Times Square: Cult Classic Revival at Chicago Filmmakers"

from OUTLINES (September, 1995)

http://www.greatgridlock.net/Trini/outlines.html

Please email

MILESAGO

if you have any extra information to add to this page

Copyright © Milesago 2003

Please report any broken links to

webmaster@milesago.com