| MILESAGO: Australasian Music & Popular Culture 1964-1975 | Features |

"AS IF EVERY NOTE WAS AN ABSOLUTE JOY"

The Story Of Charlie Tumahai

(1949-1995)

by John Low

(originally published in Australian Music Museum)

"He had a soul, a very strong personality

and he always grinned when he was playing, as if

every note was an absolute joy."

- Bill Nelson, Be-Bop Deluxe

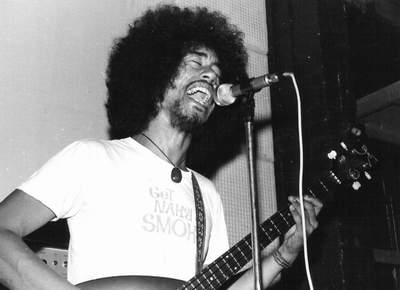

Charlie onstage at

Melbourne's Thumpin' Tum disco in 1971 with the legendary Healing

Force. (Image © Harley Parker, 2001)

Charlie onstage at

Melbourne's Thumpin' Tum disco in 1971 with the legendary Healing

Force. (Image © Harley Parker, 2001)

At the beginning of the film Once Were Warriors, as the camera moves inside the hotel and pans across the crowded interior, it rests momentarily upon a karaoke singer battling to be heard above the noise. It is something of an irony that the actor who is playing the part of this singer is in fact a professional musician who has already, during a long career, made a considerable contribution to the genre of popular music.

Over a period of something like 25 years Charlie Tumahai’s inventive, melodic bass playing and his warm, strong voice enhanced the performances of a wide variety of bands in three countries. Growing up in New Zealand, he spent the early 1970s in Australia before moving to Britain for 10 years and finally returning to New Zealand in 1985. He may never have become a household name but he was always held in the highest regard by fans and peers alike. Music was his passion and he spent his life making it.

As a fan, I have long been frustrated by having to chase sporadic references to his musical life and recorded legacy. This article, therefore, while drawing heavily on already published sources, is an attempt to bring some of this scattered information together and thereby allow his career to be seen in proper perspective.

Born Charles Turu Tumahai in 1949 in the Auckland suburb of Orakei, he was the second of eleven children to a Maori mother and a Tahitian father. Music was always a part of his childhood and the Maori show bands were a particular source of enjoyment and inspiration. He and his cousins were often allowed to attend evening concerts at the Maori Community Centre near Victoria Park. "We were looking at our heroes, it was just fantastic", he told New Zealand journalist Andrea Rush in an interview not long before his death. "I was thinking: ‘I want to play like them.' Mostly we were trying to keep our eyes open and then Uncle Jim (Watene) would carry us out to the car, take us home and put us to bed."

He began performing when he was still at school, singing at weddings and birthdays in a vocal group called The Sunbeams. This was followed by a stint as rhythm guitarist in a Top 40 covers band known as The Columbians, but his career in music took a real forward step when his family moved to Tahiti in 1966. Here he began playing bass guitar and turned professional, serving his musical apprenticeship by playing around the hotels in Tahiti and New Caledonia in cabaret bands with names like Hotel Tahiti Orchestra.

When the family again packed up and returned to Auckland

in mid-1968 he joined a Maori show band called Tekiwi with whom he

eventually traveled to Australia to play the cabaret circuit in

Sydney. In 1969 Tekiwi was offered work backing a black

American

singer named Wiley Reid on a concert tour of the military bases in

Vietnam. They embarked on this three-month tour as The Wiley Reid

Review but, on their return to Australia in the summer of 1969, Charlie

departed.

He then joined another cabaret band, Multiple Balloon; it was during this period that Charlie made his recording debut on the

two singles that Multiple Balloon recorded for Jimmy Stewart's Sweet Peach label and

for almost a year continued to work the Sydney hotel and cruise circuit

before finally leaving the cabaret scene for a career in rock music. In the second half of 1970 he began this new direction

with brief stints in two bands. The first of these was a revived

version of Sydney pop band Aesop's Fables, followed by a

temporary 6 weeks bass playing residence in Nova Express. This latter

band was originally formed in Adelaide but moved to Melbourne in 1969,

fusing pop, big band and jazz in a style similar to Blood, Sweat

& Tears.

Now in Melbourne, Charlie was invited to join what, in different circumstances, could have proved to be a musically satisfying and successful Australian band. Music historian Ian McFarlane (1995) describes the saga of Healing Force as "one of the tragedies of Australian rock music". Formed in Adelaide in October 1970, the band quickly relocated to Melbourne and, with the departure of their original bass player (John Pugh) Charlie was invited to join by the remaining members -- Lindsay Wells (guitar), Mal Logan (keyboards), Laurie Pryor (drums) -- just two weeks before their live debut. During its short life Healing Force performed on the dance circuit around Melbourne appearing at venues like Berties, Sebastians and the Thumping Tum along with such high profile bands as Daddy Cool, Billy Thorpe & the Aztecs, Spectrum and the La De Das. They also travelled to South Australia for the Myponga Festival in January 1971 and played at the Launching Place Festival in Victoria.

While jazz-rock influences were strong, like a number of Australian bands of the time they mixed a variety of styles in their performances from hard rock to psychedelic to country. Charlie brought a vocal style to the band described by McFarlane as "majestic" and "brimming with passion and strength of purpose" and, in the view of many, this contributed in no small measure to this short-lived band’s only recorded single becoming an Australian classic. That single, "Golden Miles", a song written by Lindsay Wells about life on the road, was recorded in April 1971 but, almost immediately it was released, the band began to disintegrate, ironically during an unhappy tour into NSW and Queensland.

Healing Force was a band of immense possibilities. McFarlane laments that "one can only speculate as to what this splendid outfit could have achieved with a full length album. ... Here was an exceptionally talented aggregation of musicians capable of offering audiences a soaring range of moods and styles, a band with the potential to take Australian progressive rock into hitherto unexplored territories." Though there was, in January 1973, a brief revival with Charlie joining Mal Logan, John Pugh and Laurie Pryor to play a promising set at the Sunbury Festival, Healing Force split for good in April 1973.

Following his initial departure from Healing Force, Charlie spent four or five months in the latter part of 1971 with Chain, Australia’s seminal blues/rock band through whose ranks numerous fine musicians have passed. In fact, this version of Chain included a large chunk of the old Healing Force, with Lindsay Wells and Laurie Pryor also joining Charlie. Though only of brief duration, the opportunity this residency provided to play with the likes of Matt Taylor and Phil Manning was an experience not to be dismissed.

When Taylor closed down this incarnation of Chain in October 1971 Charlie then joined with fellow Kiwi, guitarist and vocalist Leo De Castro, to form Friends. They were joined by Tim Martin (sax, flute), Duncan McGuire (bass), Mark Kennedy (drums) and for a short period by Rob McKenzie and Phil Manning. The caretaker guitar roles of the latter were eventually (by April 1972) filled permanently by Billy Green and Ray Oliver. Friends developed into a highly respected band in Melbourne and Charlie remained with them throughout 1972. Friends recorded one single during this time, on which his great soulful voice was again to the fore and to which he contributed the splendid b-side song "Freedom Train".

Charlie left Friends in January 1973 to join the resuscitated Healing Force and, when Healing Force finally called it quits, he and Mal Logan joined Tony Lunt (drums) and Tim Piper (guitar) to form Melbourne-based Alta Mira in April 1973. Playing mostly hard rock and blues, its life -- like most of his other bands to date -- was short. By November 1973 its members had gone their separate ways. At this point in his career Charlie could well have looked to be a real itinerant musician fated to a future of continuing brief residencies in go-nowhere bands of unfulfilled musical promise. However, the next move he made proved to be his ticket, not only out of Australia, but also to a period in his career of far greater stability than he had to date experienced.

Mississippi was influenced by the harmonies and guitars of America’s West Coast and was formed in Adelaide from the remnants of Alison Gros. Following the band’s relocation to Melbourne, they wer signed up by Ron Tudor's Fable label; Charlie joined Graham Goble (guitar), Beeb Birtles (guitar), Derek Pellicci (drums) and Harvey James (lead guitar) at the end of November 1973. For the remainder of 1973 and early 1974 the band committed itself to a heavy schedule. While based in Melbourne it travelled widely, performing also in Sydney, Adelaide, Perth and a variety of regional centres and recording songs for a single and an EP. Then, in April 1974, Mississippi embarked for Britain on the Fairsky and played nearly 30 concerts during the voyage, arriving in London towards the end of May.

Needless to say, the ‘old country’ did not prove to be the hoped for land of milk and honey. Just another group of unknown musicians from the colonies trying to establish themselves in England, they soon became frustrated. Harvey James left soon after their arrival and was replaced by original member, Englishman Russ Johnson, but the move proved ultimately unsuccessful and the band played its last gig on 17th August 1974 at Hatchetts Nite Club in London. While Charlie decided to remain in Britain, the remainder of the band returned to Australia where Goble and Birtles went on to form the highly successful Little River Band.

It was still a pre-punk London in which Charlie found himself unemployed, a rock music melting pot where bands mixed and matched and experimented with new styles and images. The Britain of the first half of the 1970s was the realm of David Bowie and his alter ego Ziggy Stardust, of Hawkwind, Soft Machine, Yes, King Crimson, Queen, Gong, Emerson, Lake & Palmer and numerous other artists promoted as progressive, glam, space or whatever else they chose to call themselves. It was, according to your particular point of view, either a musically exciting, progressive period or a time of bloated, self-important pretension ripe for the taking when the infidels inevitably stormed the gates.

Whatever, when Charlie responded to an advertisement in Melody Maker for a bass player to join Be-Bop Deluxe and turned up for an audition at a small rehearsal studio somewhere in London, he certainly looked the part. "I had these tight white jeans on", he told Andrea Rush, "six-inch stack-heeled alligator boots and my hair out like Jimi Hendrix." Bill Nelson and Simon Fox of Be-Bop, who were conducting the auditions, were clearly impressed. Nelson remembered that “after listening to many bass players who were OK, but nothing special, suddenly Charlie turned up. He just seemed head and shoulders above everyone else who had auditioned. It wasn’t just that he was more musical than the others, he seemed more suitable, more 'right' for the band." They all retired to a nearby café for a chat and by the time the coffee was drunk Charlie had the job.

Bill Nelson, the band’s founder and leader, hailed from Yorkshire and had been playing in and recording with a number of local bands until influential British DJ John Peel heard one of his solo albums, gave it air time and helped attract the interest of EMI. The result was the formation of Be-Bop Deluxe and a migration south. By the time Charlie was recruited on bass in late 1974 the band had already gone through two versions that didn’t satisfy Nelson. However, when Charlie and then Andrew Clark on keyboards were added to drummer Simon Fox, Nelson was satisfied he had found the combination he wanted and this line-up remained stable for the next four years.

Commonly described as an ‘art rock’ band, Be-Bop Deluxe was primarily a vehicle for Nelson’s guitar wizardry and intelligent song writing. It was Nelson’s band; the songs were his, melodic and lyrically interesting, delving regularly into fantasy and science fiction, and his flamboyant guitar playing generally dominated the music. While it seems fairly clear that the other musicians were there to support his creative vision, Nelson was well served by three talented and, when given the space, innovative musicians.

Indeed, this incarnation of Be-Bop proved a lyrically thought provoking and musically accomplished band that recorded four studio albums (keyboard player, Clark, was recruited following the first), a ‘live’ album and numerous singles and achieved a reasonable degree of commercial success without ever quite breaking through into the really big time. Their principal fan base was in the UK and Europe and, though they toured America and had large audiences on both coasts, the wider US market eluded them.

In 1975 Charlie’s temporary work permit expired and, during 1976-77, he was forced to enter a lengthy appeals process to remain in Britain. Despite arguing that he was an essential element in the band’s music, it appeared that he would be prevented from re-entering the country if Be-Bop went ahead with a planned tour of America. When all channels of appeal seemed exhausted and Charlie was told to leave Britain, the band made plans to relocate to France. Indeed, by the time he received a last minute reprieve and his work visa was renewed, the band had gone ahead and hired a villa in the south of France, along with the Rolling Stones’ mobile studio, and had begun recording what would ultimately become their final album.

In an interview following Charlie’s death, Bill Nelson described him as "a big, warm-hearted, life-loving man" and a "really good, musical bass player" possessed of a great voice and "an energetic stage presence …[that] added an extra dimension" to their live performances. He then summed him up in that delightful sentence quoted at the head of this article: "He had a soul, a very strong personality and he always grinned when he was playing, as if every note was an absolute joy."

Following the release of Drastic Plastic in 1978, Bill Nelson decided that Be-Bop had run its course. He had already begun thinking of a new musical vehicle for his creative vision and, on bringing Be-Bop Deluxe to an end, was simultaneously bringing Red Noise into being. Charlie was out of a job once more and, with the demise of Be-Bop Deluxe, the pattern set in Australia of brief tenures in short-lived bands, along with the inevitable sense of unfulfilled musical promise, threatened to repeat itself.

The first band he joined was Hollywood Killers, a band seemingly poles apart musically from Be-Bop Deluxe. Though little information survives, it has been described by one internet fan as a “legendary punk/powerpop” band. Led by Hastings musician Jim Penfold, the Killers played in London and also around the Hastings area and there may also have been a couple of gigs in Europe. They recorded and released a single in 1978 and it is quite probable that Charlie played on this. Charlie’s wife, Sue, remembers the band as being “a great favourite at society functions”. Nonetheless, he soon moved on.

The Dukes were formed in mid-1979 and was an assembly of very experienced musicians who had played supporting roles in a variety of successful bands, a ‘sidemen’s super group’ if you like. The original line-up included Miller Anderson (guitar, vocals) formerly of the Keef Hartley Band, Jimmy McCulloch (guitar) of Wings, Ronnie Leahy (keyboards) of Stone the Crows and Charlie of Be-Bop Deluxe. They recorded an album in mid-1979, added a permanent drummer in Nick Trevissick from the Tom Robinson Band, made their debut in London at the end of September and set out on an autumn tour of Britain. It was not long, however, before fate dealt a telling blow. In late 1979 their lead guitarist Jimmy McCulloch died from a heroin overdose and while the band reformed with replacement guitarist Mick Grabham (formerly of Procul Harum) their future proved bleak. They persevered into 1980, touring with Wishbone Ash in February and, though one critic described their sound as “bold and clean, utterly confident”, they disbanded soon after.

For several months in 1980 Charlie ‘trod water’ in two very brief tenures with minor league bands. First, he worked for a short spell with a three-piece known as McKitty. Named after its guitarist Donovan McKitty, the band is probably most notable for the fact that it also included the future Iron Maiden drummer Nicko McBrain. They played around London and toured with Brian Robertson’s (ex Thin Lizzy) band Wild Horses. It’s doubtful if McKitty ever recorded and certainly not while Charlie was with them.

After McKitty came Score, formed by an Irish musician Josh McAuley and Mike Montgomery, formerly of Chapman-Whitney Streetwalkers. They gigged around London for a time, even recording a single, but wider success eluded them and Charlie eventually drifted back into an association with Miller Anderson. Sue Tumahai recalls some sessions where Charlie, Miller and ex Rolling Stones guitarist Mick Taylor worked together, though she doubts they ever played any gigs.

Charlie and Miller Anderson then joined ex Jethro Tull drummer, Barriemore Barlow, to form Tandoori Cassette. The Dukes’ keyboard player, Ronnie Leahy, was also recruited along with ex Sensational Alex Harvey Band guitarist, Zal Cleminson. As with his early Australian band Healing Force, Tandoori Cassette was to prove a case of great potential sadly unrealised. The band only lasted through 1981 and eventually broke up sometime in 1982. According to Sue Tumahai, it was "a terrific band" and one of Charlie’s most musically satisfying experiences. They toured and did quite a bit of recording at Barlow’s own studio, set up in the barn at his home. However, while a number of bootlegs containing demos and live recordings have circulated, only one official recording was ever released.

For the remainder of his time in England Charlie appears to have occupied himself musically with periods of session work and there was also, in the words of Sue Tumahai, “a fledgling band that never left the nest”. His life in the UK was winding down and a new chapter, in which a major re-assessment of his life and a re-discovery of his Maori self would occur, was about to begin.

The question is often asked: Why did Charlie Tumahai move through so many bands? Was he inherently restless and difficult to work with? Not according to fellow New Zealander Mal Logan who played with him in Healing Force and Alta Mira. "He was one of the easiest people to work with", he told Ian McFarlane when asked if Charlie was "a volatile guy in any way". Logan suggested that the reason he would "jump around from band to band quite a bit" was "not because of his attitude, it was more a question of survival".

This is borne out by Bill Nelson, in whose band Charlie spent four stable years. Admitting that he did have "a wild side", Nelson went on to say that "we got on very well and when he was with me he was always a perfect gentleman. A real asset to the band generally." As has been noted, when it looked like Charlie might be refused an extension of his British work permit, so highly did the other band members regard him that Be Bop Deluxe made preparations to relocate permanently to the south of France.

When his post Be-Bop Deluxe bands failed to stay together, it clearly depressed him a great deal and probably played a part, along with other personal matters, in convincing him to return to New Zealand. Bill Nelson describes a meeting he had with Charlie not long before he left Britain. He apparently rang Nelson and then visited him during the recording of one of the latter’s solo albums. "At the time, I think he was working on a fruit and veg stall", Nelson recalled. "When he came down to the studio he seemed a little bit down with living in England ... I think he had become a bit more worldly-wise after suffering a few hardships. He was definitely down from working with bands who hadn’t stayed together very long. Maybe he worked with the wrong people. He deserved better, that’s for sure."

And 'better' he got when he returned to New Zealand in 1985 and linked up with the rock/reggae band Herbs, described by Chris Spencer [1989] as "NZ’s most soulful, heartfelt and consistent contemporary musical voice." Formed by his cousin, guitarist Dilworth Karaka, in 1980, the line-up during Charlie’s time included Thom Nepia (percussion), Tama Lundon (keyboards), Morrie Watene (saxaphone) and Gordon Joll (drums). In the decade he was with them they released two studio albums, a ‘best of’ album, guested on the recordings of friends like Tim Finn and Dave Dobbyn ("Slice of Heaven"), supported numerous overseas artists on tour in New Zealand and contributed to the soundtrack of Once Were Warriors.

Though popular in their own country, Herbs gained an enormous following throughout the South Pacific with lyrics that expressed an anti-nuclear and pro-land rights political stance. When they head-lined an international rock/reggae festival in New Caledonia in 1990, deep in the heart of pro-independence Kanak territory, a crowd of over 3000 turned up to dance and sing along. Ironically, six months earlier the French Government had forbidden them from doing a concert tour in Noumea on the grounds that they were ‘subversive’.

In all his British bands Charlie never appears to have had the vocal opportunities he experienced early on with bands like Healing Force and Friends. He sang back-up vocals but the lead was always left to others. This situation was remedied when he returned to Auckland. His expressive voice and melodic bass playing fitted into the Herbs and their music perfectly. His song writing also flowered again and he remained a principal member of the band until his death.

In fact, this was possibly the most fulfilling period of his whole career. In his interview with Andrea Rush he said of his return to New Zealand: "I discovered I needed guiding back into my Maori self again. I needed to become a New Zealander again. I realise now the Maori side of me helped me get my feet back on the ground. It was a steady force, a steady influence." As well as music he became involved in Maori affairs, working as a voluntary member of a scheme set up to assist young Maori offenders in Auckland. He was also developing plans for an arts program for Maori prisoners and for exploring new ways he could help young Maori connect with their culture when, on 21 December 1995, he collapsed and died of a heart attack while working at the Auckland District Court. He was only 46.

Charlie's death came as a complete shock to his family and friends. He had cycled and practiced yoga regularly and appeared to be leading a physically and mentally healthy life. After a service at the Orakei Marae Charlie was buried at the Okahu Bay cemetery, Auckland, on 24 December 1995. New Zealand and the music world generally were left the poorer for his passing. He will continue to be remembered and honoured by all those around the world who have been touched by his music.

Select Discography

1971 - Healing

Force

"Golden Miles" / "The Gully" (Sparmac)

Aug. 1972 -

Friends

“B.B. Boogie” / “Freedom Train”

(Festival)

Apr. 1973 -

Various Artists

The Great Australian Rock Festival - Sunbury

1973 (3-LP)

[Festival/Mushroom]

- includes “Erection” by the briefly revived Healing

Force

1973 - Various

Artists

Garrison: The Final Blow

Unit 2 (LP) (Mushroom)

- includes Alta Mira’s only recording "My Soul’s On Fire"

1974 -

Mississippi

“Will I?” / “Where in the

World” (Bootleg)

1974-

Mississippi

Will I? (EP) (Bootleg)

May 1975

- Be-Bop Deluxe

Futurama (LP) (Harvest/EMI)

Reissued as EMI CD 1991, with additional tracks.

Jan. 1976 -

Be-Bop Deluxe

Sunburst Finish

(Harvest/EMI)

Reissued as EMI Cd 1991 with additional tracks

Oct. 1976 -

Be-Bop Deluxe

Modern Music

(Harvest/EMI)

Reissued as EMI CD 1991 with additional tracks.

Aug. 1977

- Be-Bop Deluxe

Live! In the Air Age

(Harvest/EMI)

Reissued as EMI CD 1991 with additional tracks.

Feb. 1978 -

Be-Bop Deluxe

Drastic Plastic

(Harvest/EMI)

Reissued as EMI CD 1991 with additional tracks.

Dec. 1978 -

Be-Bop Deluxe

The Best of …

and the Rest of Be-Bop Deluxe

(Harvest/EMI)

1978 - Various

Artists

The Bootleg Special

(Bootleg)

- includes Mississippi’s "Will I?"

1978-

Hollywood Killers

"Goodbye Suicide" / "The Tramp"

(Rollerball)

1979 - The Dukes

The Dukes

(Warner Brothers)

1980 - The Dukes

"Leavin’ It All Behind" / ? (Warner Brothers)

1980-

Score

“Wash House” / “Skin of My

Teeth” (label unknown)

1982 - Tandoori

Cassette

"Angel Talk" / "Third World

Briefcases" (label unknown)

1986 - Dave

Dobbyn

Footrot Flats: The

Dog’s Tale (Soundtrack) (CBS)

includes "Slice of Heaven" and "Nuclear

Waste", the latter song performed solely by the Herbs.]

1987 -

Herbs

Sensitive to a Smile

(Warrior)

1990 -

Herbs

Homegrown

(Tribal)

1993 -

Herbs

Best of ... 13 Years of

Herbs (Warner Music)

Feb. 1994 -

Be-Bop Deluxe

Air Age Anthology

(EMI)

1994 - Various

Artists

Golden Miles: Aussie

Progressive Rock 1969-1974 (Raven)

Includes Healing Force's "Golden Miles" and

Friends' "Freedom Train"

1994 - Various

Artists

The GTK Tapes Vol.1 (ABC/EMI)

includes a live 1971 TV studio recording of Healing Force “My

Boogie”

1994 - Be-Bop

Deluxe

Radioland BBC Radio 1

Live in Concert (Windsong International)

Recorded 1976.

1994 - Various

Artists

Once Were Warriors

(Soundtrack) (BMG/Milan)

Herbs perform "Homegrown" and wrote “Here

Is My Heart”.

1994 - Various

Artists

Other Enz: Split Enz and

Beyond (Raven)

includes the Tim Finn and Herbs track "Parihaka".

References / Links

SPECIAL

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

I would like to express particular thanks to Sue Tumahai

who very generously read a draft of the article, answered various

questions by email and letter and sent copies of clippings from her

personal scrapbooks. Any errors and omissions in the above, however,

are all mine.

- John Low

PRINT SOURCES

Anon

“The Dukes, Charlie Tumahai”, profile in Warner

Brothers’ publicity handout accompanying the release of The

Dukes’ album in 1979.

Anon

“Herbs’ Political Reggae Live in New

Caledonia”,

New Zealand Express, 24 January-6 February

1990.

Anon

“Band Leader Dies Suddenly”,

The New Zealand Herald, 22 December 1995.

Anon

Notice of Death,

The New Zealand Herald, 23 December 1995.

Bradley, Grant

“Singer Leaves Potent Message”,

The New Zealand Herald, 23 December 1995.

Dix, John

Stranded In Paradise: New Zealand Rock

‘N’ Roll 1955-1988 (Paradise

Publications, 1988)

Hodkinson, Mark

“Bill Nelson and Be-Bop Deluxe”,

Record Collector, No.220 December 1997.

Larkin, Colin, ed

The Guinness Who’s Who of Seventies Music

(Middlesex, England: Guinness Publications, 1993)

McFarlane, Ian

The Encyclopedia of Australian Rock and Pop

St. Leonards, NSW: Allen & Unwin, 1999.

McFarlane, Ian

Freedom Train: Aussie Progressive Rock 1970-1976

Vol.1, Issue 2, 1995.

[Contains an in-depth study of Healing Force that includes an interview

with Mal Logan. Also an article on Chain.]

McFarlane, Ian

Freedom Train, Vol.1, Issue 3,

Special Collectors Edition: The Australian Progressive, Hard Rock and

Blues Record Guide, 1996.

McGrath, Noel

Noel McGrath’s Australian Encyclopaedia of

Rock & Pop (Adelaide: Rigby, 1984)

Nelson, Bill

Editorial & Interview (19th June 1996)

in Nelsonian Navigator, Issue 3, Summer 1996.

Rush, Andrea

“The ‘Mad Maori’ Who Was Born to

Perform”

Sunday Star Times, 7 April 1996.

Spencer, Chris

Who’s Who of Australian Rock, 2nd

ed. (Fitzroy, Victoria: Five Mile Press, 1989)

Spencer, Chris et.al

Who’s Who of Australian Rock, 4th

ed. (Noble Park, Victoria: Five Mile Press, 1996)

Spencer, Chris

Rockin’ & Quakin’ in New

Zealand, 2nd ed. reprint (Golden Square, Victoria: Moonlight

Publications, 2000)

Strong, M.C.

The Great Rock Discography, 3rd ed. (Edinburgh, UK:

Canongate Books, 1994)

York, William

Who’s Who in Rock Music (London: Arthur

Barker, 1982)

One of the few reference books to include an entry on The Dukes.

Beeb Birtles’ web site http://www.birtles.com

Graham Goble has compiled a complete chronological concert listing for every incarnation of Mississippi. You can find it at: http://www.lrb.net/goble/liveshows1.htm

Permanent Flame: The Bill Nelson Web Site

http://www.billnelson.com

The primary source for information about Be-Bop Deluxe. The site

includes a

comprehensive discography and the Nelsonian Navigator editorial and

interview with Bill Nelson listed above.