"It's all about

crooked

cops, dirty politics and one big cover

up."

"It's all about

crooked

cops, dirty politics and one big cover

up." | MILESAGO: Australasian Music & Popular Culture 1964-1975 | Features |

THE JUANITA NIELSEN CASE

"It's all about

crooked

cops, dirty politics and one big cover

up."

"It's all about

crooked

cops, dirty politics and one big cover

up."

At about 11am on July 4, 1975, publisher, activist and heiress Juanita Nielsen left her terrace house at 202 Victoria Street, Kings Cross. She was on her way to a well-known Kings Cross nightclub, The Carousel Cabaret, where she had an appointment to meet the manager, Edward Trigg. Ostensibly the meeting was to discuss advertising for the club in her local newspaper, NOW. She was never seen again.

Like the Wanda Beach murders and the disappearance of the Beaumont children, the Nielsen case remains one of Australia's most enduring mysteries and the background to exposes the dark side of life in Sydney. Perhaps because it involved a wealthy heiress it was also one of the first cases to focus wide public attention onto the sinister nexus of big business, big money, development, official corruption and organised crime.

There have been many newspaper articles written about the case and numerous books and films written about or based on it. A 1983 jury inquest and a 1994 Federal Joint Parliamentary Committee both looked into Juanita's disappearance, but no charges were ever laid as a result of these proceedings. The 1983 inquest concluded that she was probably dead but that it was not possible to say how, when or where she died. The jury also added a significant rider to its findings:

"There is evidence to show that the police inquiries were inhibited by an atmosphere of corruption, real or imagined, that existed at the time."

More than a quarter of a century later Juanita's exact fate is still unknown. It is a virtual certainty that that she was murdered on or about July 4 1975, but the time, manner and place of her death are unknown and her body has never been found. Her killer or killers are presumably still at liberty and no one has ever been directly charged with planning or causing her death. Three men were eventually charged with her abduction in 1977. Two served a total of five years and one was acquitted. Those who ordered the crime, if they are still alive, remain at large and unpunished.

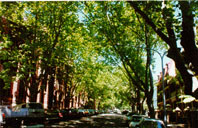

The

setting for these dramatic events was Victoria St in the famous inner

city suburb of Kings Cross, just east of the CBD. Perched on the edge

of a sandstone escarpment, with million-dollar views westward to St

Mary's Cathedral, Hyde Park and the city and north to the harbour,

Victoria Street is located in an area once referred to as the

"Montmatre of Sydney". This beautiful avenue is lined with huge

overarching plane trees and flanked by rows of elegant 19th century

terrace houses. Its tranquil beauty belies the fact that it's only a

few blocks from the seedy heart of Sydney's red light district.

The

setting for these dramatic events was Victoria St in the famous inner

city suburb of Kings Cross, just east of the CBD. Perched on the edge

of a sandstone escarpment, with million-dollar views westward to St

Mary's Cathedral, Hyde Park and the city and north to the harbour,

Victoria Street is located in an area once referred to as the

"Montmatre of Sydney". This beautiful avenue is lined with huge

overarching plane trees and flanked by rows of elegant 19th century

terrace houses. Its tranquil beauty belies the fact that it's only a

few blocks from the seedy heart of Sydney's red light district.

In the early '70s, Victoria St became a focal point in a long-running struggle against urban redevelopment. On one side were the powerful forces pro-development forces in local and state governments and ambitious, greedy property developers. On the other were the inner city residents who sought to preserve the character of their historic suburbs. From the late '60s onwards, the battle raged all over the city

It was a hard and sometimes violent struggle. Some areas like The Rocks suffered and Redfern and Wooloomooloo were substantially damaged, but countless houses and other buildings were saved from destruction. The turning point in the battle came in the early '70s when resident action groups gained a powerful ally -- militant building union the Builders Labourers Federation (BLF). Under a progressive new leadership headed by Jack Mundey the BLF underwent a revolutionary expansion of its customary role as workers' representative, which saw the union explicitly align itself with conservationists and resident action groups to oppose developers. The BLF imposed an innovative series of work bans -- soon dubbed 'Green Bans' -- to combat the developments planned for many inner Sydney suburbs.

The Green Ban movement began with the pioneering 1971 ban on a planned housing development at Kelly's Bush in Hunter's Hill, which was the last remaining large tract of uncleared bushland on the lower Parramatta River. Green Bans proved tremendously successful in halting the thoughtless exploitation of these historic areas by the state government, Sydney City Council and property developers by preventing any worker in the union-dominated building and demolition industries from working on any banned site, effectively halting much of the planned development for years to come. Indeed, many of these areas, notably The Rocks and Victoria Street, owe their continued preservation to the BLF's progressive stance.

What made the bans imperative was the rapidly growing pressure for development in NSW. At the time the Green Bans began, the state led by Robert (Robin) Askin, leader of NSW's first Liberal state government, which came to power in May 1965. The city skyline had already risen dramatically, following the 1957 abolition of the old ordnance limiting city building heights, set in 1912. In the late '50s and early '60s the Labor state government and Sydney City Council (both long dominated by the Labor Party) also began to draw up plans for a massive modernisationand redevelopment of inner city suburbs and the CBD.

Had they been fully enacted, these plans would have destroyed huge tracts of Victorian-era terrace housing in the inner city. Most of these areas are now prestige inner city suburbs, where house prices are now calculated in the millions. but back then, they were depressed, run-down and alrgely working class suburbs, widely regarded as slums. Targets for "redevelopment" included large tracts of Redfern, Newtown, Glebe, Surry Hills, Darlinghurst, Potts Point, Woolloomooloo, Pyrmont, Paddington and Kings Cross, and parts of these suburbs had already been the focus of major "slum clearances" in the early 1900s. Following overseas trends, it was planned that the old "tenements" would be replaced by Modernist high-rise tower blocks, similar to those which blight many European and American cities, and which are now being progressively demolished. Some high-rise blocks were indeed built, most in Redfern and a few in Glebe and Newtown. The development schemes also included an American-designed plan for a massive new freeway system to serve the central city, which would have seen huge arterial roads driven through the historic hearts of these suburbs.

Development in Sydney reached unprecedented levels under Askin, who ruled until his retirement in 1975. Australian state administrations have long struggled with corruption but NSW was perhaps the worst-affected of all and many believe that Askin's regime deliberately promoted a dramatic strengthening of the links between government, business and organised crime. It is now widely accepted that Askin was one of the most corrupt politicians in recent NSW history. He has been reliably and closely linked with major criminals, oversaw a vast expansion of police corruption, reputedly sold knighthoods for cash, and had imtimate connections with the notoriously venal NSW racing industry, including the scandal-ridden Waterhouse bookmaking dynasty.

Investigative reporter David Hickie claimed that Askin -- an illegal "SP" bookie in his younger days -- was paid bribes of at least $100,000 per year and that his "cut" included a huge payoff collected by a bagman from the city's leading SP bookies once a month at the City Tattersall's Club. Australia's draconian defamation laws shielded Askin and his cronies until just after his death, when he was finally exposed by David Hickie and David Marr's groundbreaking report in The National Times -- controversially published the day before Askin's funeral in 1981 -- and by Hickie's landmark book The Prince and The Premier. Askin’s corruption was proven after his wife's death, when her vast estate revealed wealth far in excess of her late husband’s reputed legal earnings.

The floodgates of CBD and inner urban development in Sydney opened in 1967 when the Askin government took a highly controversial step. They were under pressure to open up the city to more development, and they were keen to do so, but to realise these plans they needed to break the ALP's stranglehold over Sydney City Council. The key to problem was city boundaries. In 1948 the Labor state government had controversially redrawn the boundaries, enlarging the City of Sydney to over 11 square miles and bringing in many inner-city suburbs which had formerly been part of the old County of Cumberland. This had many effects, but the most salient feature was that these new wards were mostly working-class residential suburbs which not coincidentally were overwhelmingly pro-Labor in their voting habits. The new boundaries enabled Labor to dominate Sydney City Council for almost twenty years.

Askin's was intent on crushing Labor's control, and immediately after taking office in May 1965 he appointed a Boundaries Commission, whose obvious purpose was to reset the boundaries to their pre-1948 status. Much to Askin's chagrin, the Commission initially found that there was no need to change the boundaries back, so he ordered it to draw up new boundaries, which it duly did. Sydney's planning policies -- or the lack thereof -- were by now becoming a hot issue, but the matter was taken entirely out of Council's hands in September 1967 when Askin's Boundaries Bill was introduced into Parliament. When it became law in November, the Sydney City Council was dismissed and a tribunal of administrators was appointed in its place.

The three new bosses were all loyal Askin men -- former Liberal Party leader Vernon H. Treatt, AGL General Manager William Pettingell and former Main Roads Commissioner John Shaw. The new boundaries dramatically reduced the size of the city, cutting its area by more than half from 11 to 5.2 square miles and its residential population from 171,000 to 68,500. A new city council, South Sydney, was created to administer the inner-west suburbs of north Newtown, Erskineville, Redfern, Alexandria, Waterloo and Darlington (now largely obliterated by the ever-encroaching Sydney University). Outlying areas were hived off to neighbouring municipalities -- part of Paddington was joined to Woollahra, Glebe to Leichhardt, and Camperdown and south Newtown to Marrickville.

As was undoubtedly the intention, Askin's "reforms" had a seismic impact on planning and development in the CBD and surrounding suburbs. Any pretence of a rational planning policy was abandoned and "The Three Stooges" eagerly fulfilled the wishes of their masters, rubber-stamping an unprecedented flood of new development applications between 1967 and 1969. According to civic historian Paul Ashton, only Administrator Pettingell had any interest in planning matters and he effectively became the sole arbiter of development approvals. John Doran, quoted in Ashton's book, gives a depressing account of the conduct of city planning meetings during the "interregnum":

"If you got there after the bell stopped reverberating you missed the meeting, because that's about how long it took. They'd ring the bell, say the prayer, adopt a paper and close the meeting and walk out. Anthing over thirty seconds was a long meeting. John Shaw had personal hates about buildings. He didn't like black buildings. So people quickly learnt to put in light-coloured buildings. That was the sort of measure of planning expertise that was around at that time. It was mostly personal ideas."

In mid-1969, with new council elections looming, rumours spread that the city planning policies were to be radically revised. This sparked a frantic rush of applications from developers keen to get their plans approved before the supine regime of the administrators ended. The monthly building approval rate during this period skyrocketed by more than 400%, from a peak of about 10 per month in 1968 to than to almost 50 per month in mid-1969 -- to this day, the highest figure in the city's history.

Askin and his developer mates also had their covetous eye on the prime real estate in The Rocks and to ensure that planning responsibility for this lucrative prize was kept well out of council's hands, Askin established the Sydney Cove Redevelopment Authority (SCRA) in 1968, giving the new body total planning power over the area. SCRA's controversial approval of plans for huge residential and commercial developments sparked a desperate battle to save this most historic precinct.

The development rush continued apace even after a new city council was elected in 1969, and not surprisingly the new Civic Reform administration was strongly pro-Liberal and pro-development. Under the City of Sydney Strategic Plan published in 1971, another massive commercial redevelopment was planned for Woolloomooloo, but helped by the Federal Government and the BLF Green Bans, the Woolloomooloo Resident Action Group (WRAG) managed to avert wholesale demolition and acquire some low-income medium density housing.

Areas like The Rocks, Woolloomooloo, Kings Cross and Potts Point were especially attractive to developers. With its unequalled location on the eastern side of Sydney Cove, The Rocks was one of the most sought-after areas for development, and it was ripe for the picking. It had a longstanding reputation as one of the worst slum areas in Sydney, was the source of a major bubonic plague outbreak in the 19th century and had been home to the notorious "Rocks Push", the vicious street gang that ruled the area in the late 1800s.

Other more affluent suburbs had only gradually declined and some still retained a air of decaying gentility. Although little evidence remains today, the peninsula east of the city -- originally called Woolloomooloo Point now Darlinghurst/Kings Cross/Potts Point -- was actually Sydney's most prestigious address for much of the 1800s. In 1828 and 1831 Governor Darling made large land grants to leading figures in the colony and a string of seventeen palatial villas (some by famed colonial architect John Verge) were built along the promontory. Set in huge gardens of up to ten acres, these magnificent estates ran down the ridge from William Street down to Potts Point; the leafy character of the area owes much to their sumptuous gardens, stocked with exotic plants collected from around the world. The attraction was obvious even in the 1830s: it was only a short distance from the city, with spectacular sweeping views of the city and harbour to the east, and north, and out to the Blue Mountains in the west, but it was far anough away from the noise, smell and bustle of the town to make it a highly sought-after locale.

Gradually though the great estates were broken up and subdivided, and one by one the maginificent houses were torn down to make way for terrace houses, flats, hotels, and theatres. Some were destroyed in the late 1800s, some lasted into the 1920s and '30s and one survived until as recently as 1966. Today only a handful remain including "Tusculum" and the magnificent Elizabeth Bay House.

But by the 1960s, the north shore and the harbourside suburbs further east had long since taken over as the new prestige areas. The rather seedy reputation of these now inner-city areas, their run-down condition and their predominantly lower-income populations made it relatively cheap and easy to buy up substantial amounts of property. Another influential factor in the Kings Cross area was the construction of the long-delayed Eastern Suburbs Railway, which finally began in the late '60s and was well underway by the early '70s. A station was planned for the veyr centre of the Cross, directly under the site of the former Kings Cross Theatre, which became famous during the '60s as the music venue Surf City. The only major obstacle to development, the city council, had been effectively removed by Askin and by the turn of the decade developers were poised to begin a massive reshaping of the city.

The

person who came to embody the battle against development in Kings

Cross was 37-year-old Juanita Nielsen. A committed social activist,

Juanita was the heiress to the Mark Foys retail fortune. She became

passionately involved in the fight to preserve the character of Kings

Cross and used some of her wealth to start her own newspaper, NOW,

through which she led a crusade against vice, organised crime and

development in Kings Cross.

The

person who came to embody the battle against development in Kings

Cross was 37-year-old Juanita Nielsen. A committed social activist,

Juanita was the heiress to the Mark Foys retail fortune. She became

passionately involved in the fight to preserve the character of Kings

Cross and used some of her wealth to start her own newspaper, NOW,

through which she led a crusade against vice, organised crime and

development in Kings Cross.

Theeman had already spent millions acquiring property in the street, but as soon as the plans became public Kings Cross residents and supporters rose up and mounted organised resistance to the development. Vigorous attempts were made to coax or bully the residents into selling up. When that failed, a gang of heavies (reputedly under the supervision of notorious ex-detective Fred Krahe) was brought in. They threatened and intimidated residents, and on several occasions they 'roughed up' anti-development protesters who converged on Victoria St,while police stood idly by. In one incident, merchant seaman and jazz singer Mick Fowler, a resident and leading member of the anti-development campaign, returned from a period at sea to find that all his personal effects had been removed from his house. Fowler fought a protracted court battle to stay in his home and the strain of the struggle reputedly led to his early death at the age of 50 in 1979. But bolstered by the key support of the BLF, Juanita and NOW, the Victoria St residents held out against the developers.

The battle for Victoria St reached its peak in 1975. The Green Bans had been highly effective in stalling development in Kings Cross and many other areas, but the BLF's radical stance enraged developers, the government and conservative elements in the union movement, who were all determined to stem the BLF's influence. In 1975 Jack Mundey as his supporters were deposed by the BLF federal executive (led by the notoriously corrupt Norm Gallagher) and the new conservative BLF leadership immediately lifted the ban on Victoria Street, leaving Nielsen and her neighbours to fight on alone. NOW and Juanita became virtually the sole voices of opposition to the development.

Given the vast sums involved in the proposed development the stakes were very high indeed. According to the Sydney Morning Herald, by mid-1972 Theeman had spent almost $6 million buying up property in the street. He planned to spend another $40 million developing the site and was reported to have been losing $1 million a year in interest payments because of the Green Ban. On this basis alone, when considering the question of who stood to gain from Juanita's disappearance, Theeman must surely be considered a prime suspect in the conspiracy to silence her. His involvement became even more probable in light of evidence given to the 1983 inquest, which showed that Theeman had intimate connections to key figures in Sydney organised crime.

Juanita's fateful appointment at the Carousel on July 4 took her into the heart of that underworld. The man she was to meet, Edward Frederick Trigg, was the night manager of the Carousel's VIP Bar. He also had a long criminal record including convictions for stealing, receiving stolen goods and living off the earnings of prostitution.

The Carousel Cabaret was one of many clubs, bars, pubs and other businesses, both legal and illegal, owned or operated by reputed czar of organised crime Abraham "Abe" Saffron, who was said to control a major underworld network that encompassed illegal gaming, prostitution, sly grog shops, drugs and protection rackets. The Carousel was managed by Saffron's notorious deputy James McCartney "Big Jim" Anderson who later testified against his former boss before the Wood Royal Commission into organised crime. Anderson had a fearsome reputation as a "heavy" around the Cross. In 1970 he allegedly shot and killed standover man Donny "The Glove" Smith but the Askin government mysteriously dropped the manslaughter charge soon after Anderson's committal hearing.

Alongside Frank Theeman, Jim Anderson must be considered as the other prime suspect in the Nielsen case, although he has always vehemently denied any involvement, claiming that he was in Surfer's Paradise at the time of Juanita's disappearance.

In testimony before the 1983 inquest Anderson named the notoriously corrupt Sydney policeman Det. Sgt Fred Krahe as Juanita's killer. His claim was echoed by freelance journalists Tony Reeves and Barry Ward but there was no evidence to support it. Krahe -- reputed to have been one of the most dangerous policemen in NSW in his day -- had died in 1981, so it was a safe bet for Anderson to finger him -- and given Krahe's reputation it's doubtful that even Anderson would have done so if was still alive. By then it was also widely rumoured that Krahe had killed anti-drugs campaigner Donald McKay in 1977 and that he had close connections to the infamous Nugan-Hand bank and the Griffith Mafia.

The 1994 Committee was also told that it was Krahe who had

organised the gang of heavies that threatened residents refusing to

sell out to Theeman and beat up protesters. Krahe was also well known

to both Saffron and Anderson and was a regular client at another of

Saffron's clubs, The Venus Room. The Committee was told "There was a

widespread rumour that Krahe had killed her."

Both the 1983 jury inquest and the 1994 Federal Joint Parliamentary Committee heard evidence that Frank Theeman and Jim Anderson had extensive social and business associations and that Anderson was "mentor to Theeman's drug-troubled son, Tim". Addressing Anderson's alleged role in the crime the 1994 Parliamentary Committee found that:

" the adequacy of the police investigation" (into who ordered Juanita's murder) "can be questioned, as can the (police) conclusion that there were no further leads to be followed up. Despite the evidence linking Anderson with Ms Nielsen's disappearance, the attempt by police to investigate the role of Anderson seems to have been cursory."

Of particular note in this regard was evidence tendered to the 1983 inquest that Theeman's family company FWT Investments paid Anderson $25,000 in May 1975, just two months before Juanita disappeared. Anderson claimed that the cheque was an "advance" for the purchase of a club in Bondi that he was buying in Tim Theeman's name. However at the inquest, the owner of the club in question testified that no money had ever changed hands. Furthermore, a 2001 report in the Sydney Morning Herald claimed that after giving Anderson the cheque Frank Theeman panicked about the likelihood of the payment being traced and that he unsuccessfully tried to borrow money from Abe Saffron to cover it.

According to the Herald, Theeman continued to fund various of

Anderson's business ventures and according to CrimeNet the 1994 Federal

Joint Parliamentary Committee heard evidence that Theeman "loaned"

Anderson a total of $260,000 over the years. The 1994 Committee further

concluded that Anderson was a "prime suspect" in the Nielsen case and

that there was a "view that Anderson was blackmailing Theeman (and)

this was related to the disappearance of Nielsen".

From evidence given to the various investigations into the case, it is clear that there were at least two other attempts to threaten or abduct Juanita prior to July 4 and in 2001 former Carousel receptionist Loretta Crawford, who had remained silent since 1976, came forward with new claims about the case.

Before June 1975 the Carousel had no direct connection with Juanita or NOW, but that month Jim Anderson initiated contact by sending Juanita an invitation to attend a press night at the club on June 13. According to the Herald, she would not normally have been invited because NOW did not give free publicity. In the event, Juanita did not attend and both Crawford and Trigg have said that Anderson was "furious" about her nonappearance.

A few days later Trigg instructed the Carousel's PR man Lloyd Marshall to invite Juanita to a meeting at the Camperdown Travelodge, supposedly to discuss advertising related to landscaping. Nielsen was suspicious and refused to attend.

On June 30, four days before the Carousel appointment, Trigg and another man, Carousel barman Shayne Martin-Simmonds, called at Juanita's house on the pretext of inquiring about advertising the Carousel's businessmen's lunches in NOW. It was later claimed that in fact Trigg and Martin-Simmonds intended to seize Juanita when she opened the door, but their plan was foiled when her friend David Farrell answered the door instead. The two men played out the cover story, but Nielsen was listening in an adjoining room and after they left she complimented Farrell on his handling of the query, teasing him by saying she might send him out on the road to sell advertising in NOW.

Interviewed by police on November 6 1977, Martin-Simmonds confirmed that the advertising story was a ruse and that their actual intention was to kidnap Juanita if she was alone and take her to see "people who wanted to talk to her". He said that he and Trigg intended to:

"... Just grab her arms and stop her calling out, no real rough stuff, no gangster stuff. We thought that just two guys telling her to come would be enough to make her think if she didn't come she might get hurt ... we talked about when she came into the room, one of us would be standing there and the other one would come up behind her and and just quietly grab her by the arms and maybe put a hand over her mouth or a pillowslip over the head."

Not surprisingly, Juanita was by then seriously concerned that her activism was putting her in danger. She mentioned her fears to Farrell about two weeks before her disappearance and she arranged to keep him regularly informed of her whereabouts.

Precisely what transpired on the morning of July 4 will probably never be known but it's clear that Juanita was lured to the Carousel with at least the intention of threatening and/or abducting her. Loretta Crawford says that Trigg instructed her to call Juanita on the night on Thursday July 3 to set up a meeting at the club for the following morning. Crawford now claims that she knew that the advertising story was "bullshit" since the club did not advertise in "local rags", that she was doubtful that Juanita would attend, and that she was surprised that Juanita kept the appointment.

At 10:30am on Friday July 4 Juanita telephoned David Farrell to tell him that she was running late for the meeting. It was the last call she would ever make. According to Crawford, when Juanita arrived she proceed to the landing on the first floor where Crawford's reception desk was located. Crawford offered her a seat and a cup of coffee, after Juanita remarked that she had had a "hard night", but says Juanita didn't get to drink the coffee because Trigg arrived. Crawford noted that he was on time, which she said was unusual since he was often late. He and Juanita exchanged greetings on the landing and went upstairs to Trigg's office.

At this point in her account, given to the Sydney Morning Herald in 2001, Loretta Crawford made a startling new claim -- that she then made a phone call to Jim Anderson at his home in Vaucluse, told him that Juanita had arrived and that he was "quite pleased" by the news. Crawford was adamant that she was in no doubt whatsoever that Anderson was at his home in Vaucluse, not in Surfer's Paradise as he has always claimed.

When interviewed by police in 1977, Anderson claimed as his alibi that he flew to Surfer's Paradise with another man on July 4 and stayed there for about three days in a room booked in his wife's name at the Chevron Hotel. Significantly, police never checked out any details of his alibi other than the fact that his car, which was left at Sydney Airport, had received two parking tickets. As Crawford rightly says, this proved only that Anderson's car was at the airport. According to the Herald, police neither contacted the man that Anderson claimed accompanied him to Surfers, nor did they verify whether he in fact Anderson flew there on that day with TAA.

When first questioned in 1975, Trigg told police that Juanita left the club by herself after their meeting. However, 18 months later Loretta Crawford changed her story and told police that Juanita left the club with Trigg but that she was told to say that Nielsen had left on her own. Police also discovered later that Shayne Martin-Simmonds was seen at the Carousel that day. Crawford said that although she didn't see him herself, she was told of Martin-Simmonds' presence at the club by Trigg's girlfriend, later that day.

Crawford now claims that after the meeting Juanita and Eddie Trigg came downstairs, past her booth on the first floor landing of the club. Seconds later, she says, Trigg doubled back and out of Nielsen's sight said: "If anyone asks, sweetheart, we didn't leave together."

After Nielsen and Trigg walked down the stairs and out of Crawford's view, they would have come to another landing. Just off that landing, out of view of the front door, was a steel-grille door which led downstairs to a locked storeroom. In recent years, the Herald says, police have shown interest in the storeroom, but after so many years the chances of finding any evidence - if there ever was any - is almost zero. It is particularly notable that the police did not investigate the club at the time Juanita disappeared.

When first interviewed by police in 1975, Loretta Crawford had confirmed Trigg's version of events -- that he and Nielsen parted company on the first floor landing of the club. But as noted above, when re-interviewed in 1976 she changed her story, saying that Trigg and Juanita left together, and she then told police what she claimed Trigg had really said. She now says that she didn't tell the truth at first because she was in fear of Jim Anderson. She says Juanita was under no duress when she left.

A possible scenario is that Martin-Simmonds was waiting on the lower landing when Juanita and Trigg came downstairs, where they seized her and took her downstairs to the storeroom. Whether she died there or elsewhere is unknown.

The exact circumstances of her presumed death and the whereabouts of her remains will probably never be known, but after 25 years it's a virtual certainty that Juanita was murdered, possibly in the storeroom at the Carousel. Evidently her body was efficiently and completely disposed of and no direct evidence of the crime has ever been found.

Rumours abound as to her fate. It's been variously claimed that she was buried under the Third Runway at Sydney Airport, that her remains were ground up and fed to pigs at a farm on the city outskirts, disposed of at sea, or buried in the foundations of a city building.

The only thing known for certain is that she was never seen again after she left the Carousel. The only physical evidence ever found after July 4 were her black handbag and some of her personal effects. These were found a week later on July 12, dumped beside a freeway in western Sydney. A large and intensive police search of dams and rivers in the area found nothing else.

Whether Juanita's death was deliberate is also unknown, although there have been several claims that her death was simply "an accident", perhaps a case of a standover tactic that went too far. But there are plenty of reasons to suspect that her death was intentional. Her dogged and costly opposition to a huge property development was an obvious motive, and even Anderson had to admit that he was a logical suspect. Certainly people have been killed for far less than the millions involved in the Victoria Street project.

But Juanita also campaigned actively against vice in the Cross and it has been claimed that she was about to release evidence exposing leading figures involved in Sydney's organised crime scene. As Sunday reporter Ross Coulthart points out "the biggest problem faced by investigators was that so many people had so many reasons for wanting her dead." The inquest was told that her opposition to vice and development made her a thorn in the side for crime bosses and developers alike.

Her boyfriend, John Glebe, gave evidence that Juanita had told him about receiving telephone threats and testified that she carried cassette tapes in her handbag. According to Glebe, Juanita had told him that the tapes could "blow the top off" an issue she was working on. In his book Connections - Crime Rackets and Networks of Influence Down-Under [Sun Books, ISBN 0 7251 0491 0] investigative journalist Bob Bottom reported that after her disappearance, Mr Glebe received a threat from anonymous phone caller, who said: "Juanita has been killed ... it was an accident. Back off, or accidents can happen to other people."

In 1976 journalists Barry Ward and Tony Reeves released a media statement saying their investigations into the Juanita Nielsen case had uncovered a police cover up and they implored Premier Neville Wran to set up a Royal Commission into the police investigation. Their plea was ignored so the two journalists sent a telegram to Wran on July 22, 1977. In part the telegram said:

"We are dismayed and disgusted at your

refusal to conduct a

Royal Commission into the murder of Juanita Nielsen and the subsequent

cover-up of that event. One of the significant points your announcement

neglects to

consider is that the police officer upon whose advice the Government`s

conclusions are based was involved significantly in the original

investigation about which we made allegations of a cover-up.

We will continue in our campaign for exposure of then truth

in this affair, despite your Government`s cowardice to come to grips

with this most serious issue. We will explore and expose numerous other

references of police impropriety to their fullest. It is shameful that

we will have to embarrass this

Government into action."

In late 1977, two and a half years after she disappeared, Trigg and two others were finally arrested and charged with conspiring to abduct Juanita. Trigg absconded in 1981 while on bail awaiting trial but he was eventually recaptured in the US in 1988 and deported to face trial. He pleaded guilty and was gaoled for three years. The second suspect, Shayne Martin-Simmonds, was convicted in 1981 and was gaoled for two years. The third man, Lloyd Marshall, the Carousel's "PR man" in 1975, was acquitted.

Ever since there has been a persistent sense in the community that the full story of the Nielsen disappearance has never come out, and that the facts of the case have been hidden under a cloud of corruption. Ross Coulthart reports that when Trigg was caught in the US, he allegedly said: "It's all bloody politics, anyway ... It's all about crooked cops, dirty politics and one big cover up. The guy who is benefiting from this is an alderman who made megabucks out of this."

In 1995 The Bulletin magazine ran claims by Barry Ward that Juanita had been given dossiers on some "prominent Sydney identities" by private detective Allan Honeysett. The article speculated that these documents could have lifted the lid on the principals involved in Sydney's illegal gaming industry. Honeysett claimed these documents were the real reason why Nielsen was killed -- because it appeared likely she was about to expose big names involved in vice and illegal gambling. The Bulletin story also interviewed two anonymous female staffers who had been showgirls at the Carousel in 1975. They named three men who did the murder and the story went on to detail how the men who ordered the murder are still at large.

In 1998 NSW police reopened the case after a witness came forward with new information. The witness claimed that her flatmate had confessed to her that he was Nielsen's killer. Police flew to London to interview the suspect but to date no charges have been laid as a result of this new investigation, although the case remains open to this day. The same is true of Loretta Crawford's new allegations, printed in the Herald on July 1 2000.

The facts and implications of the Nielsen case reverberate in the Australian psyche and over the years it has left a strong imprint on local culture. It has been examined in many newspaper articles, numerous nonfiction books, formed the basis for several novels including Dave Warner's Big Bad Blood and Mandy Sayers' The Cross, and also directly inspired at least two feature films.

Donald Crombie's The Killing of Angel Street (1981), explored corrupt official involvement in a city property development, from local police to the highest levels of government. Phillip Noyce's Heatwave (1983), also clearly based on the Nielsen case, starred Judy Davis as an Juanita-type activist battling development in an inner city, low-income neighborhood.

A quarter of a century later, the lasting testament to Juanita Nielsen is Victoria Street itself. Through her efforts, and those of her neighbours and supporters, many of the beautiful terraces were saved, and her memory lives on as a champion of social activism and responsible, human-centred development, and as someone unafraid to stand up against the forces of crime and corruption.

In March 2001 the Greens party launched the Juanita Nielsen Memorial Lecture series, an annual lecture series commemorating the work of women activists. Announcing the series, Greens MLC Lee Rhiannon said that it was important that the contemporary Green movement realised that many of the battles against corruption and for democracy are re-runs of past controversies.

In July 2008 Abe Saffron's only son Alan returned to Australia from his home in the USA to promote his memoir Gentle Satan: My Father, Abe Saffron. The book reportedly names former Saffron associate Jim Anderson as the chief agent of the conspiracy to silence Nielsen (although Anderson consistently denied any involvement while he was alive). In his interview with Lisa Carty of The Sydney Morning Herald, Alan Saffron said that he had received death threats over the book because it would name some of the people involved the conpsiracy, but that he was unable to name everyone involved for legal reasons, because come were still alive.

Saffron claimed the people he could name people "much bigger" than former NSW premier Bob Askin and one-time police commissioner Norman Allan, with whom his father corruptly dealt to protect his gambling, nightclub and prostitution businesses, and he specifically referred to:

"... one particular businessman I was desperate to name, and there's one particular police officer who is extremely high ranking. They're the biggest names you can imagine in Australia".

According to the Herald article, all the conspirators are named in the original manuscript of the book, which is now in the possesion of Saffron's publishers, Penguin, and that the book will be re-published after as the others allegedly involved in the Nielsen case die.

References / Links

Paul Ashton

The Accidental City:

Planning Sydney Since 1788 (Hale & Iremonger,

1993)

Sydney City

Council Electoral History

http://www.cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au/hs_chos_electoral_history.asp

ninemsn "Sunday"

investigative files

http://news.ninemsn.com.au/sunday/investigative/case2.asp

Sydney

Morning Herald

http://old.smh.com.au/news/0007/01/review/review2.html

Donald McKay -

Crime Scene Melbourne

http://www.melbournecrime.bizhosting.com/dmackay.htm

Persons Missing

http://www.personsmissing.org/juanita.html

Victoria St

www.kingscross.nsw.gov.au/tour/victor.htm

Lee Rhiannon MLC

http://www.lee.greens.org.au/Spin/Spin01/Mar-Apr/s0312_nlsn.html

Mandy Sayer

http://www.thei.aust.com/sydney/biographies/sayer.html

Lisa Carty

"The only son of Mr Sin returns to scene of the his enemies"

Sydney Morning Herald,